Usage-based pricing

Usage-based pricing has been the darling of SaaS founders since Twilio, Stripe, and Snowflake broke through in the 2010s by generating monumental wealth for them and value for their customers. Ever since, investors and operators alike have tried to shoehorn consumption pricing into their products. However, there are some pretty hard and fast rules where it can be used effectively.

🪧 PSA: I’ll use the term usage or consumption pricing interchangeably from here on out, deal with it.

First, the setting

I’m not sure you’ve heard, but I’m from Maine. Coupling this with my experiences at a little company called IBM informs much of who I am today. I had the privilege at IBM to observe the disruption in the data warehouse market throughout the 2010s. First, the promise of Hadoop materialized. Everyone was excited about cheap servers and big data — until they realized it wasn’t the answer.

Spark continued the data lake promise of Hadoop, and (I guess) it’s going OK. Databricks seems to be crushing it.

Leading up to and during this period, IaaS was becoming reliable, ubiquitous and trusted. All of a sudden, you didn’t have to buy bare metal, install it in a warehouse, manage patches, pay for people to work at the data center, cool it, etc, etc, etc. New data warehousing competitors sprung up to take advantage of paying only for what you used.

I was a lowly pricing analyst for a division of IBM called Netezza. Formerly the appliance leader of the data warehouse market, Netezza was acquired in 2009 for $1.7B. They had made oodles of money ripping out db2 1, Oracle and Teradata warehouses while competing with the new columnar hotness of the time (Vertica + Greenplum).

And now, a story

As a pricing analyst, I got to be included in transactions where exceptional discounts were requested. The street price of Netezza was once ~700-800k per full 42U rack with 15% in support each year after that. A rack had about 48TB of raw storage, and you could get around ~200TB of effective space with 4x compression. Believe it or not, customers were not paying for disk space — they cared about speed, and Netezza was omega fast.

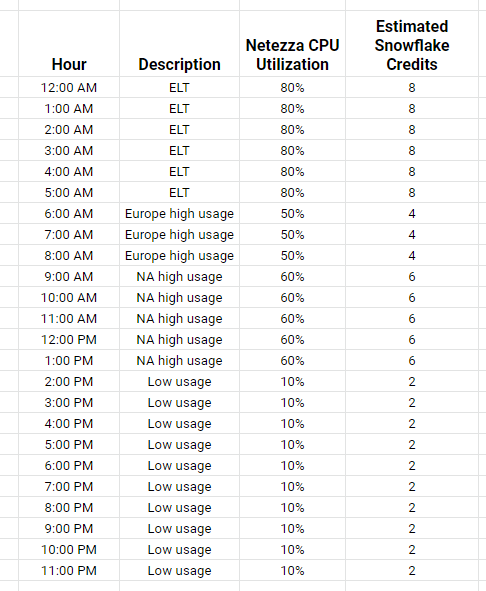

Suddenly, around 2014-2015, I started seeing significantly higher discounts on deals. The common denominator was a competitor called Snowflake. The trick with these Snowflake deals was that they would show customers a spreadsheet like this:

In competitive deals, Snowflake pricing would always be 20-30% of the TCO of an equivalent Netezza system. The problem wasn’t that one performed worse than the other. Core-for-core, Netezza actually performed better than Snowflake at the time. The problem was that Snowflake could scale up and down at will — taking advantage of IaaS elasticity and costs.

This allowed Snowflake sellers to make a stupid spreadsheet like the above, take Netezza logs, plug them in, and then make a cost-savings play because Snowflake pricing is consumption-time based. Of course, buying a 112-core system and sticking it in a data center will be more expensive than renting 200 cores in someone else’s data center for 6 hours a day.

🕒 Believe it or not, many Netezza customers had ELT periods of 6+ hours. They paid millions of dollars to make up for poor data engineering skills.

Snowflake ended up eating Netezza alive. IBM eventually killed the platform in favor of a columnar db2 appliance, and the migration was a nightmare for customers with tons of data ingestion and stored procedure tech debt. In 2020 they resurrected “Netezza Performance Server”, and I’m honestly not sure how it is doing. Looks like some people are using it.

In retrospect, Snowflake was always going to win. As soon as it became clear that IaaS was cheaper and more reliable than your own on-prem servers, it was only a matter of time before even the oldest and most conservative of companies would move to Snowflake/BigQuery/Redshift.

🥇 Why did Snowflake win among the big 3 cloud DWs? Pre-2019, Redshift didn’t have good autoscaling or stored procedure support. BigQuery based their pricing on TB scanned or slots, both of which the market kind of hates. Google also spent a long time in the early 2010s focusing on something other than SQL which, while it may seem bananas now, was not that crazy when everyone thought Java was going to be the data engineering language of choice.

Similar dynamics happened for Stripe & Twilio. Formerly expensive, chunky things like payment processing and text messages were disrupted by applying IaaS to the problem and making it attractive with 10x cheaper TCO enabled by a usage metric.

When should you use usage-based pricing?

There’s a ton of hype around usage-based pricing, and even more companies trying it out over the past few years. I think way too many companies have tried forcing consumption pricing where it doesn’t make sense — ThoughtSpot being a fantastic example. Generally, the further you are from infrastructure on an incremental basis, the less sense usage-based pricing makes sense.

The story that I told focused very much on cost. In general, usage-based pricing makes the most sense when it allows customers to save money. This is easiest to see in the earlier example: Snowflake was objectively core-for-core slower (at the time), yet it won because it applied IaaS scalability principles — and therefore saved people money with a usage-based metric.

1) Usage-based pricing is a good primary metric for saving people money based on what they were doing before

If you aren’t saving people money, you’re going to start to run into the classic consumption pricing problems:

- Charges aren’t predictable

- Metric confusion (what’s a Credit ™️?)

Only when you can tell a slam-dunk story around cost savings will the sins of usage-based pricing be forgiven.

Take GitHub for example. Git collaboration platforms save companies millions of engineer hours yearly. However, there hasn’t historically been a huge Git collaboration line item for enterprise software budgets. GitHub probably wishes they could charge per merged PR or something like that, but they can’t — because there’s no easy existing bill to point to and say, “See! You’ll only pay 20% of this with us.”

2) Capture the whale with usage-based pricing as a secondary metric

While you might not be a great candidate for usage-based pricing as a primary metric, you can still include it in your pricing tiers as a secondary metric.

B2B SaaS has always relied on the whales to effectively monetize. In following with the Pareto Principle, a disproportionate % of revenue comes from a very small % of clients. This is the concept of a fat tail.

Usage is probably a part of your product, but you may inhibit adoption based on the objections above. The solution is to place a usage-based cap on your pricing tiers. If a team or organization can embed your product with accessible pricing, they’re more likely to hit usage caps on whatever tier they are on. Once usage caps are breached, then the usage metric can flip to your primary metric on a client-by-client basis.

You’re betting on the 0.1% of companies that will embed your product to the extent that they need outsized usage and are willing to pay an outsized amount for that usage. At that point, it becomes a necessity for their business model and usage-based pricing becomes a value-add as opposed to an objection.

So now what?

Your product is unique, and if you follow these rules without thought you’re going to fail. At early stages, experiment with pricing by talking to prospective users. At mid-to-later stages, talk to your existing customers or introduce different pricing metrics/caps into new deals. At all stages, don’t be afraid to change your pricing until you find what works for you.

Have a different take? I want to hear about it.

-

A previous version of this had a typo, where dbt was listed instead of db2. Big shoutout to Emil Christensen for the catch! ↩